By Sam Dantzler

This year’s Patterson Crisis Simulation was truly one to remember, especially against the backdrop of recent events. Centered on the ongoing Russia–Ukraine conflict, the simulation included delegations from Russia, Ukraine, the United States, Turkey, the European Union, and China. As the Head of Delegation from team Ukraine, the challenges our team faced were plentiful and the experience was fraught with adversity. Going into the simulation, our team was very practical about the reality that Ukraine faces in this ongoing war. While committed to upholding our strength and sovereignty, our primary goal for this summit was to stop the bloodshed in Ukraine, even if it meant making concessions to both the U.S. and Russian delegations. This proposition proved to be even more difficult than we anticipated.

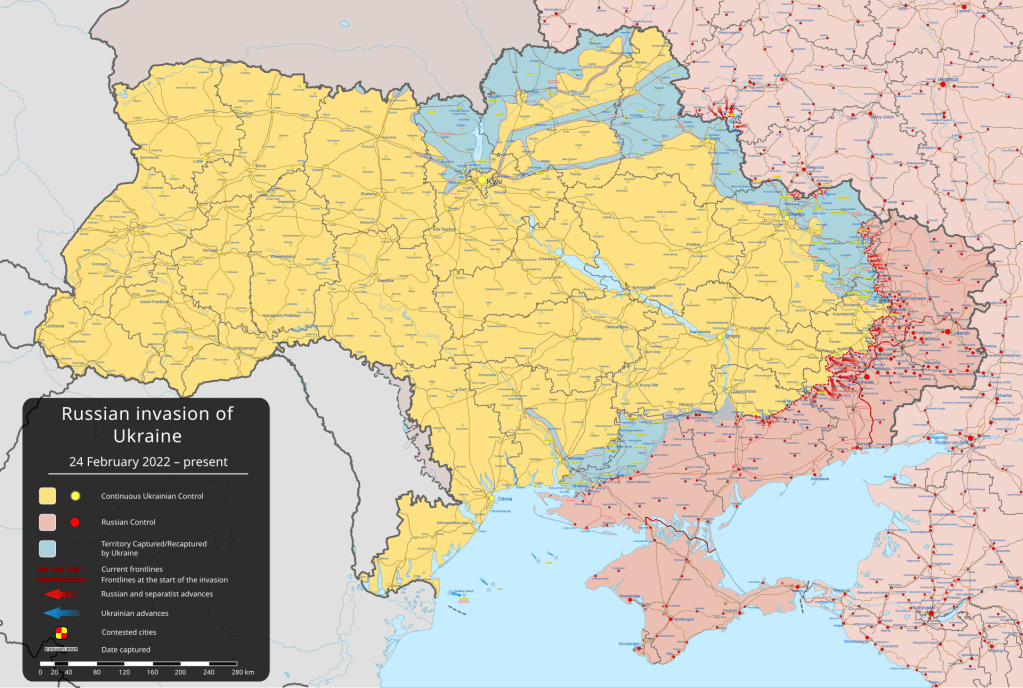

This year’s simulation was structured differently than previous ones, giving teams two adjudication rounds before the initial summit negotiations began. In these adjudication rounds, teams were able to act as heads of state and take diplomatic, economic, intelligence, and military actions to set the stage for the actual negotiation rounds. From the Ukrainian perspective, these adjudication rounds were challenging to navigate, as we had to carefully balance avoiding escalation before peace negotiations with preparing defenses against potential future Russian aggression should negotiations collapse. To do this, we worked clandestinely with the European Union delegation to place troops in strategic locations to hopefully thwart further Russian incursions that may have happened during negotiations. Similarly, our team took strategic military measures to reinforce defenses at key transportation hubs, particularly along the northern Belarusian border and around Kyiv.

Our team recognized the U.S. delegation’s sentiments, which in most cases accurately reflected the current Trump administration’s stance on Ukraine. This was a huge point of contention throughout the simulation. From the beginning, our team set a crucial red line: we had to conclude negotiations while retaining American economic and military support given the state of conflict. Simultaneously, we emphasized the need for Ukraine to align with Europe by collaborating closely with the European Union delegation and pursuing a path toward EU membership. These two pursuits proved to be at odds for most of the simulation.

As we began the negotiation rounds as the special delegation from Ukraine, we continued our steadfast commitment to two key objectives: securing American support and collaborating closely with the EU and other stakeholders to achieve lasting peace. As the negotiation rounds progressed, it became evident that neither the American nor Russian delegations were inclined to support our proposal of involving the European Union, Turkey, and China in establishing a ceasefire agreement as a precursor to formal peace talks. Adding to the complexity was Moscow’s initial refusal to permit an official meeting between the Russian delegation and our team to discuss a ceasefire. As we began exploring alternative avenues to secure a ceasefire, such as threatening to have Russia forfeit EU-held assets, the first round of negotiations was drawing to a close.

At that moment, we faced an ultimatum from both the U.S. and Russian delegations. In a meeting with them and the UN secretary at the summit, we were warned that without a prompt ceasefire, Ukraine’s role in future peace negotiations would be virtually eliminated. Although we were deeply uneasy proceeding without our close partners, the EU and Turkey, with whom we had worked so closely throughout the day, we had set another critical red line early on in our adjudication rounds.We could not allow a peace deal between the U.S. and Russia to be finalized without Ukrainian involvement, a reality that was quickly emerging. (I cannot understate how uncomfortable we were with preceding without conferring with our allies). We made the difficult decision that to secure a genuine long-term peace deal that included our allies in the next round of negotiations, we first had to reach an agreement with the U.S. and Russia at that moment. We anticipated the push back from our allies after the initial cease-fire was agreed upon, but knew we had a better chance reconciling that relationship rather than force our way back into the U.S.-Russia led negotiations the following day.

The negotiations the following morning proved less fruitful, largely because our delegation needed to smooth things over with our European and Turkish allies. At the same time, we aimed to include the Chinese delegation in the discussions, seeking to secure as many long-term security guarantors as possible. Unfortunately, conflicting interests and goals among these delegations made this objective challenging to achieve. At the same time, widespread civil unrest was widespread across Ukraine as citizens protested the agreed-upon initial ceasefire deal, while the threat of a potential military coup also threatened our national stability. Feeling that we were at a complete disadvantage in negotiations, we decided to blow up a joint meeting involving our delegation, the Russian delegation, and the United States delegation. Our strategy was to shift blame onto the Wagner group or some other Russian coalition, thereby rallying international support as Russia violated the ceasefire agreement. We hoped that the breach of the agreed-upon ceasefire would prompt the United States to mobilize its full military and financial support for Ukraine, a key condition of the initial agreement. This unfortunately did not come to fruition, as the United States delegation, which had been infiltrated by a Russian asset, decided to cut off all military aid and financial support in light of the attack.

This experience has deepened my respect for the diplomatic process and highlighted the impossible challenges that heads of state face, especially during times of war. From the Ukrainian perspective, the proposition is daunting. Negotiate your country’s future and sovereignty, but understand that your key leverage lies in security guarantees and aid from nations like the EU, the U.S., and China, countries that aren’t necessarily excited to collaborate with one another, especially in today’s global climate. Your alternative is to commit to a war of attrition, a strategy that will inevitably claim thousands more lives of your citizens. I came out of this simulation with a host of new insights and perspectives. First, I needed a drink. Second, I found myself perplexed by how heads of state, UN General Assembly members, and other key international figures navigate the complex minefield that is international diplomacy. As these negotiations play out in real life, I hope that the human cost of such devastating conflicts will be genuinely acknowledged and not just used as banter to score domestic political wins, especially in the U.S. I also hope that the actual heads of state involved in these negotiations—especially American leadership—will approach these discussions in good faith. They must recognize the importance of upholding long-established international principles of sovereignty while working to achieve a legitimate and just end to the bloodshed that has ravaged Eastern Europe over the past three years.