By Ben Trammell & Sam Dantzler

Richard Attias once said, “Sport is a great equalizer that can build bridges, transcend borders and cultures, and render even the fiercest conflicts temporarily irrelevant.” In this sense, sport undoubtedly helps shape the world around us, offering a rare commonality between diverse cultures; therefore, facilitating commonplace levers of international relations, such as soft power, diplomacy, and economic exchange.

Historical examples underscore the capability of sport to unite even the most bitter rivals. One of the most compelling examples is the role of America’s pastime in fostering rapport between occupying American forces and local Japanese service members following the end of the Second World War. Japan and the United States share a long history of exchanging baseball visits, beginning in 1905 when Waseda University’s team toured the U.S., later reciprocated by Babe Ruth’s famous 1934 visit to Japan. Unfortunately, after the outbreak of World War II, pro-war, anti-American factions in Japan whitewashed baseball’s history and limited Japanese players’ access to the sport.

It was not until after the war — following a brutal Allied island-hopping campaign, the firebombing of Tokyo, and the introduction of atomic weapons — that baseball reemerged as a unifying force in the Pacific. Just months after the conclusion of the war, the same U.S. Marines who fought at Iwo Jima began playing baseball games with a local team in Saga City, Japan, a place that had itself been the target of Allied bombing campaigns. What started as a lighthearted competition to pass the time during the Allied occupation created a widespread cultural exchange that helped normalize political relations between the two nations. Recognizing the potential to assist the rebuilding effort, General Douglas MacArthur prioritized the restoration of baseball stadiums in Japan, many of which had been converted into air defense batteries during the war. By September 1945, an American Army baseball team was touring Japan, playing games against local opponents with proceeds intended to support war orphans.

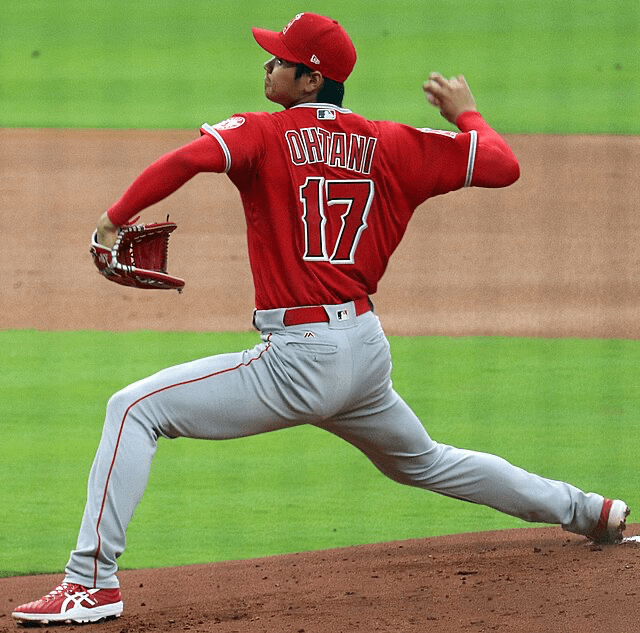

Today’s massive viewership of Major League Baseball (MLB) in Japan is the culmination of the legacy of “diamond diplomacy.” MLB games consistently attract over 2.2 million Japanese viewers, due in large part to retired and active superstars like Ichiro Suzuki and Shohei Ohtani. Furthermore, Japan has undoubtedly revolutionized the game of baseball. Two-way (pitcher and position player) Ohtani continues to prove a longstanding baseball myth woefully inaccurate, that one player can’t hit and pitch at an elite level. Since the start of his MLB career in 2018, Shohei Ohtani has recorded a .281 batting average in 3,685 at-bats, with 1,037 hits, including 274 home runs. On the mound, the three-time MVP has demonstrated consistent excellence, posting a 3.06 earned run average and a winning percentage of .661 while averaging 110 strikeouts and 86.2 innings pitched across six seasons.

Since Ohtani’s move from the Anaheim Angels to the Los Angeles Dodgers, MLB viewership in Japan has increased 42%, and the Dodgers’ World Series win over the New York Yankees set a record in Japanese viewership of 12.1 million, rivaling U.S. viewership at 15.8 million. Ohtani’s economic impact, often referred to as “Ohtanomics,” has generated a booming merchandising market, advertising revenue, and sponsorship deals. According to CNBC, MLB merchandise sales in Japan have increased over 170%, with Dodgers-branded products reaching sales highs of over 2,000%. Furthermore, the Tokyo Series generated over $35 million in revenue, a standalone highlight of baseball’s role as a niche commercial bridge. As a result, Forbesvalued the Dodgers franchise at $6.9 billion as of March 2025, a $2.8 billion increase since Ohtani’s signing in 2023. Ohtani and his fellow Dodger countrymen, Yoshinobu Yamamoto and Roki Sasaki, are also massive drivers of tourism. The Los Angeles Tourism and Convention Board reports that between 80% and 90% of visitors from Japan now make a stop at Dodger Stadium to catch a ballgame, and maybe even a Dodger Dog, at least once during their visit.

Additionally, Ohtani’s unprecedented skills have inspired a new generation of players worldwide. From Japan to the United States, Latin America, and the Caribbean, young players are vying to become the next standout two-way player, a revelation that old-school baseball fans can’t fathom. Significantly, the fostering of youth engagement increases the globalization of sport; therefore, creating massive potential for future development, economic benefit, and cultural exchange as America’s field of dreams awaits the next international two-way superstar.

Skeptics of baseball diplomacy argue that the most notable baseball exchanges occur with countries and territories that already enjoy healthy relations with the United States, such as Japan, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Canada. However, MLB player demographics complicate this view. More than a quarter of the MLB’s roster is foreign born, with large groups from adversarial states like Cuba and Venezuela. For the United States, baseball assists to ease tensions and reshape relationships, offering leaders who might otherwise avoid direct contact an informal setting to begin dialogue.

For example, in 2016, President Obama was the first U.S. President to visit Cuba since Calvin Coolidge in 1928. While in Havana, Obama visited with Cuban President Raúl Castro to watch a baseball game between the Cuban National Team and the Tampa Bay Rays. Notably, Obama’s trip sparked a historic period of semi-normalized relations between the U.S. and Cuba. Despite Congress refusing to lift the embargo on Cuba, embassies in both countries reopened, travel restrictions eased, and bilateral cooperation expanded to address health issues, environmental protections, and trade remittances. While a ballgame at Estadio Latinoamericano is not the primary catalyst for shifts in relations, it symbolized a measurable change in the relationship between Obama and Castro, and by extension, American-Cuban relations.

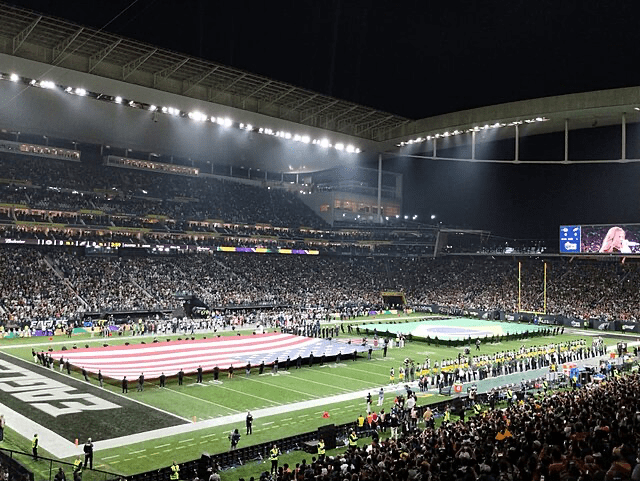

The massive expansion of American sports into international markets is not limited to the baseball diamond. Under Commissioner Roger Goodell, the National Football League has launched its most ambitious effort yet to globalize American football. When the Carolina Panthers defeated the New York Giants 20–17 in Munich, Germany, in November 2024, 70,000 fans serenaded the stadium with John Denver’s Country Roads. The game marked the NFL’s 50th international regular-season contest and capped a record five-game slate that year. Less than a year later, the Kansas City Chiefs and Los Angeles Chargers kicked off the 2025 season in São Paulo, Brazil, the first of seven international games across five countries this season, signaling the league’s intent to firmly plant its flag abroad. The NFL’s international ambitions began cautiously. Preseason contests were staged as early as 1976, when the St. Louis Cardinals played the San Diego Chargers in Tokyo’s “Mainichi Star Bowl.” Funded entirely by Frank Takahashi, a California lettuce farmer and self-proclaimed football fanatic, the game was more of a spectacle than a commercial success. Yet it laid the foundation for the NFL’s realization that exporting football would require more than one-off spectacles. True traction abroad would demand consistency, partnerships, and year-round fan cultivation.

No city has embodied this lesson more than London. Since hosting its first regular-season game in 2007, the UK capital will, by the end of 2025, have hosted 42 NFL contests. Attendance has been staggering, with many games drawing more than 80,000 fans to Wembley or Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. London’s steady stream of games, coupled with deep local partnerships, has created one of the sport’s most robust foreign fan bases. The UK’s embrace has even prompted speculation about hosting a Super Bowl or awarding the city a permanent franchise. While logistical hurdles such as transatlantic travel and competitive balance remain a real cause for concern, enthusiasm from both league and local leaders, including London Mayor Sadiq Khan, underscores the city’s growing NFL identity.

Beyond the UK, the NFL has broadened its European footprint. In 2022, Tom Brady’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers inaugurated the league’s German experiment with a sellout in Munich, drawing massive television ratings. Since then, Germany has become a regular host, with games in Munich and Frankfurt locked in through 2025. This year, the NFL will also debut in Spain, staging its first game at Real Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu. The partnership with one of Europe’s most storied football clubs fuses the NFL’s spectacle with the tradition of European sport, embedding American football more deeply in continental culture.

While Europe anchors the NFL’s strategy, Latin America represents an equally important frontier. Mexico Cityhas hosted NFL contests since 2005, consistently filling stadiums and reflecting the country’s longstanding exposure to U.S. sport. Brazil, however, represents new ground. The São Paulo series, accompanied by the opening of an NFL Brazil office and the rollout of grassroots flag football initiatives, signals the league’s commitment to Latin America as a permanent pillar of expansion. Despite criticism of field conditions and player safety during the inaugural game, the event was widely hailed as a milestone in cementing the NFL’s South American presence.

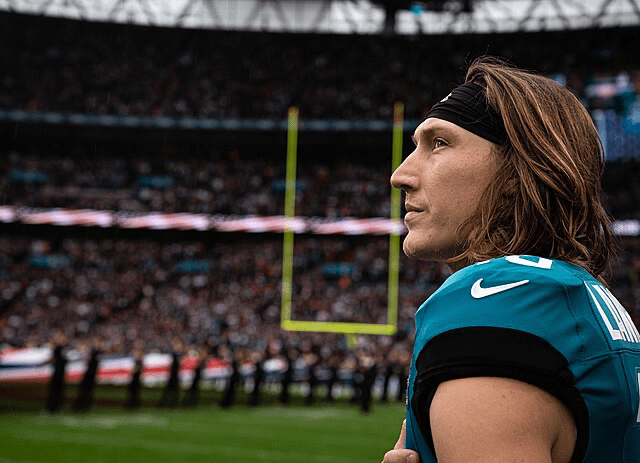

Driving these efforts is the NFL’s Global Markets Program, launched in 2021, which grants franchises exclusive marketing rights in foreign countries. Today, all 32 clubs participate, embedding themselves in local markets through youth clinics, fan festivals, commercial partnerships, and year-round media engagement. The Jacksonville Jaguars, who have played more than a dozen games in London, remain the most visible example, but teams from Seattle to Miami now treat international outreach as part of their long-term business model. The Seahawks, for example, have inked deals in Australia and New Zealand and partnered with airlines to tie their brand to regional identity. By decentralizing its international strategy, the league has leveraged its franchises to create grassroots loyalty, turning fandom into a 365-day experience rather than a once-a-year spectacle.

The NFL’s international presence represents more than business expansion; it is a vehicle of cultural diplomacy. Regular-season games abroad are staged with Super Bowl-like production, halftime shows, celebrity appearances, and branded fan events, exporting distinctly American values of entertainment, spectacle, and community. In Mexico and Brazil, where U.S. political relations are often complex, the NFL provides a rare apolitical avenue to associate the United States with excitement and aspiration rather than policy disputes. By marrying commercial ambition with cultural engagement, the NFL has positioned itself not just as a sport, but as an instrument of American soft power.

The globalization of American sports is more than a business story, it is a diplomatic opportunity. Of course, these expansions are driven by business. That was always going to happen – so why not channel that momentum to advance American interests abroad? Baseball’s deep ties in Japan and Latin America and the NFL’s ambitious expansion into Europe, Mexico, and Brazil demonstrate that American athletics can function as cultural ambassadors in ways few other institutions can match. These leagues are not merely exporting games; they are exporting narratives of community, competition, and possibility that cross cultural lines better than any other vehicle of diplomacy. Sports are universal.

What makes sports uniquely powerful is their insulation from the erosion of other soft power sources. For decades, American universities, USAID development projects, and Hollywood entertainment served as pillars of U.S. cultural influence. Yet these institutions have increasingly come under pressure from shifting domestic politics, particularly during the Trump administration, which has essentially stifled educational exchanges, completely dismantled development aid, and attacked media credibility. In this environment, the reach of American sports remains relatively untouchable. The NFL, MLB, and NBA continue to inspire international audiences not because they are government programs, but because they represent living, breathing – and most importantly, relatable – symbols of American culture.

At a time when other sports powerhouses like China and Saudi Arabia are spending billions to purchase global prestige through mega-events and athlete contracts, the United States already possesses brands with organic, generational appeal. Major League Baseball connects Tokyo to Santo Domingo, while the NFL fills stadiums from London to São Paulo. Looking ahead, the United States will also host the 2026 FIFA World Cup and the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics – two crucial opportunities to showcase America not only as a sporting hub, but as a partner in dialogue, commerce, and cultural exchange regardless of the chaos transpiring in Washington.

The lesson is clear: while traditional channels of U.S. soft power face political headwinds, American sports offer a durable, bipartisan, and globally appreciated alternative. Harnessed strategically, leagues and events can reinforce America’s image as open, aspirational, and innovative, providing a common ground for engagement even when traditional diplomacy may fail. In a moment of geopolitical turmoil and domestic uncertainty, sports may prove to be the most reliable and resonant instrument of American soft power in the twenty-first century.

Ben Trammell is a student at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce. Sam Dantzler is also a student, as well as the Patterson Journal of International Affairs writer for East Asia.

Leave a comment